21 Dirt And Dugout Homes of 1940’s Homesteaders

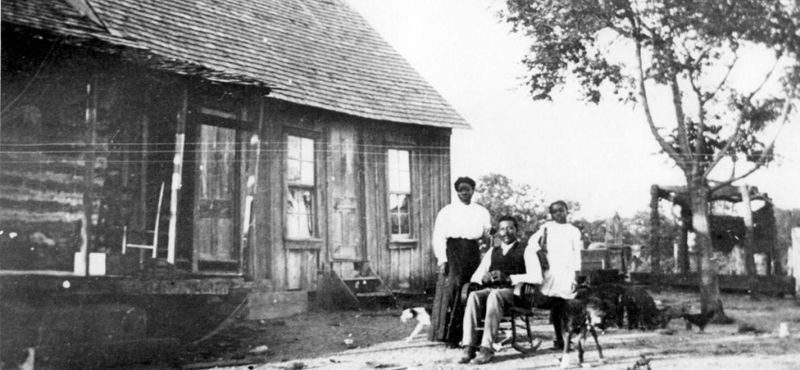

When I first stumbled upon old photos of 1940s homesteaders living in dirt homes, I was instantly captivated.

There was something ruggedly beautiful about their resourcefulness, like a real-life frontier fairytale. These incredibly hardy folks didn’t let the scarcity of bricks, boards, or nails stop them—instead, they literally carved out homes from the very earth beneath their feet!

During the Great Depression and World War II, when times were unimaginably tough, they turned to nature with grit and creativity. Their dugout homes—partially or fully underground—weren’t just clever, they were cozy!

The thick walls provided natural insulation, keeping the chill out during icy winters and the heat at bay during blazing summers. It’s like they were living in Hobbiton… only dustier and a lot more hardcore.

1. Sod House Simplicity

Wandering across Nebraska last summer reminded me of the iconic sod houses my grandmother described from her childhood. Prairie homesteaders would cut thick rectangles of densely-rooted grassland soil, stacking these natural “bricks” to form walls up to two feet thick.

The roof typically consisted of wooden poles covered with brush, then topped with more sod. Inside, residents often hung fabric on walls and ceilings to prevent dirt from constantly raining down on their belongings.

Despite their primitive appearance, these structures provided remarkable insulation against temperature extremes and could last for decades if properly maintained.

2. Root Cellar Residences

“Home sweet hole,” joked my great-uncle Bill about his first married home—a converted root cellar! Many cash-strapped homesteaders expanded existing food storage cellars into livable spaces during tough economic times.

These underground rooms, originally designed to keep vegetables from freezing in winter and cool in summer, provided ready-made shelter with minimal additional construction. Families would reinforce walls with whatever lumber they could scrounge, add proper doors, and sometimes dig light wells or small windows near the ceiling.

The constant 50-55°F underground temperature meant these homes required minimal heating even during harsh prairie winters.

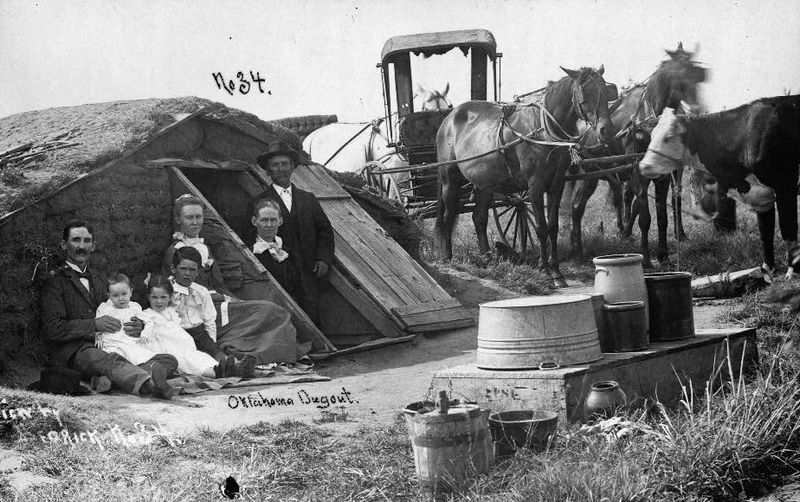

3. Bank Dugouts

While researching my family history, I discovered my great-grandmother’s first home was a bank dugout nestled against a creek embankment. These practical dwellings utilized natural terrain features by digging into a bank or bluff, creating a home that was partially underground.

The excavated portion provided the rear and side walls, while the front was typically constructed from logs, stones, or whatever building materials were available. Roofs often extended from the top of the bank over the dugout, covered with layers of brush, canvas, and dirt.

These homes offered protection from prairie winds and extreme temperatures while requiring minimal construction skills.

4. Half-Dugout Hybrids

Last month I visited a preserved half-dugout in Kansas that transported me back to the 1940s. These ingenious structures combined underground living with above-ground construction, offering the best of both worlds.

Typically, homesteaders would dig 3-4 feet into the ground, then build conventional walls extending another 3-4 feet upward. This design allowed for larger windows and better ventilation than fully underground dwellings, while still benefiting from the earth’s natural insulation.

Many families viewed these hybrid homes as transitional dwellings, planning to eventually build fully above-ground structures when finances permitted.

5. Pit Houses

The simplest dwellings I’ve encountered in my studies were pit houses—essentially rectangular holes dug into flat ground. Desperate homesteaders with few resources would excavate a pit about 3-5 feet deep and 10-15 feet across.

They’d place salvaged poles or lumber across the top, then layer brush, canvas, or tarpaper before covering everything with dirt, leaving only a small entrance and perhaps a chimney hole. Inside, the cramped space might be divided with hanging blankets for minimal privacy.

Though incredibly basic, these emergency shelters saved countless families from exposure during the harsh economic climate of the early 1940s.

6. Hill-Carved Havens

My grandfather once described these hillside dugouts as “nature’s apartment buildings.” Homesteaders would identify a suitable slope, then dig horizontally into it, creating a home with an earthen roof and three soil walls.

The front wall typically featured a wooden façade with a door and sometimes windows, allowing light to penetrate the otherwise dark interior. These homes maintained surprisingly consistent temperatures—cool in scorching summers and warm during bitter winter nights.

Residents often planted vegetation on the roof to prevent erosion and provide additional insulation, turning their humble abodes into semi-camouflaged shelters that blended seamlessly with the landscape.

7. Wattle and Daub Additions

My favorite historical dugout homes featured wattle and daub additions—an ancient building technique that experienced a revival during resource-scarce times. Homesteaders would weave flexible branches (wattle) between upright posts to form a lattice framework.

This framework was then coated with a thick mixture of mud, clay, animal dung, and straw (daub). Once dried, this material created surprisingly durable walls that could be whitewashed for a cleaner appearance.

These additions allowed families to expand their underground dwellings horizontally, creating extra living space without the expense of precious lumber or manufactured building materials.

8. Brush Shelter Entrances

Standing in front of a reconstructed dugout last year, I was struck by its elaborate brush entrance—a common feature of these humble homes. Many homesteaders created protective entryways using densely packed brush, small logs, and twigs arranged in a tunnel-like structure.

These entrances served multiple purposes: blocking harsh winds, providing a transition space between outdoors and the main living area, and creating valuable storage space for tools and supplies. During winter storms, these brush entrances trapped snow before it could blow into the main dwelling.

Some creative settlers even cultivated climbing plants around these structures, providing summer shade and additional insulation.

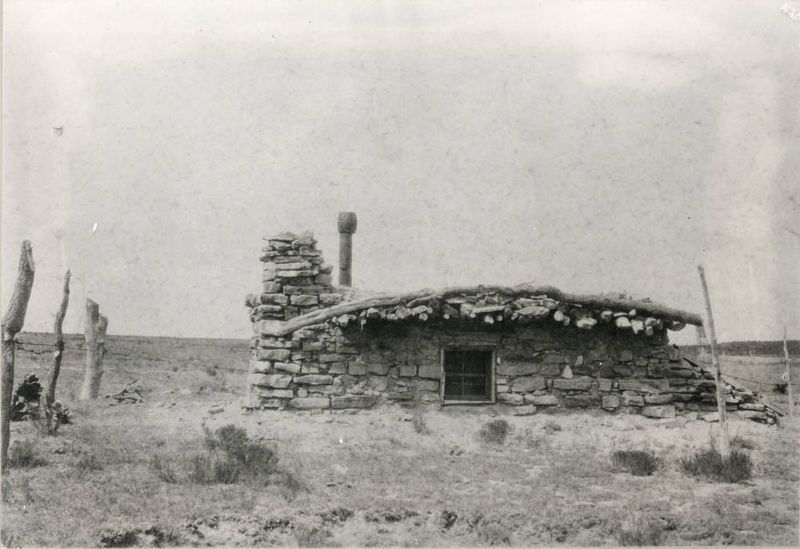

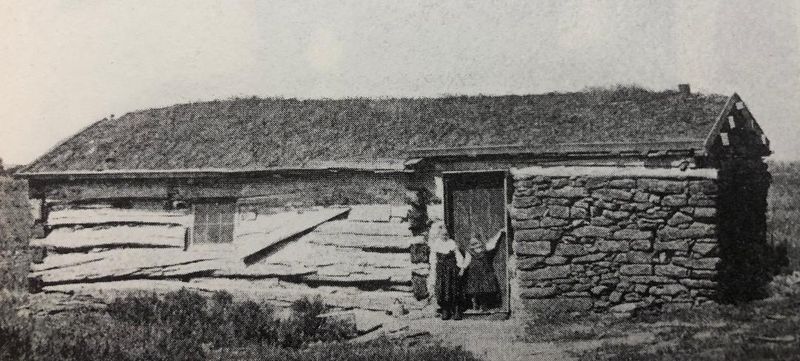

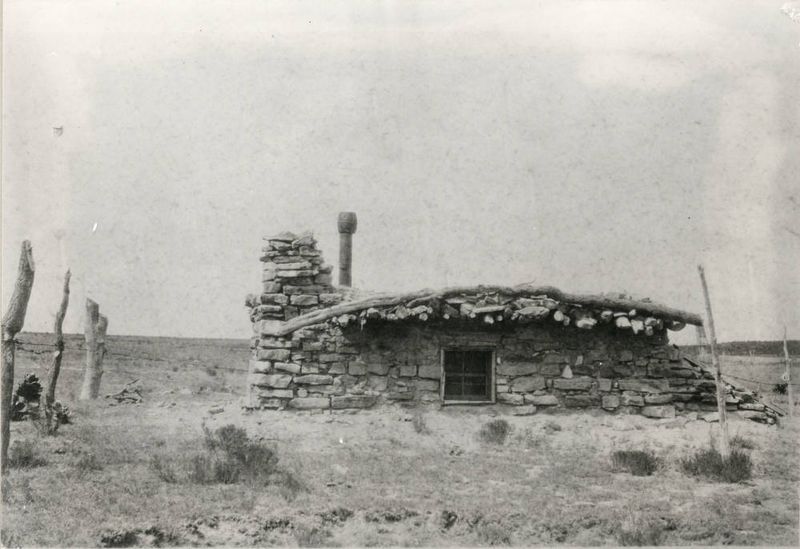

9. Stone-Reinforced Dugouts

“Rocks were free for the gathering,” my grandmother always said when describing her childhood home. In rocky regions, homesteaders incorporated fieldstones into their dugout construction, creating more durable and weather-resistant structures.

These industrious builders would collect stones from their fields (improving the land for farming simultaneously) and use them to reinforce dugout walls, build proper fireplaces, and create solid foundations. The thermal mass of stone also improved temperature regulation, absorbing heat during the day and releasing it slowly at night.

Many stone-reinforced dugouts outlasted their purely earthen counterparts by decades, with some still visible on the landscape today.

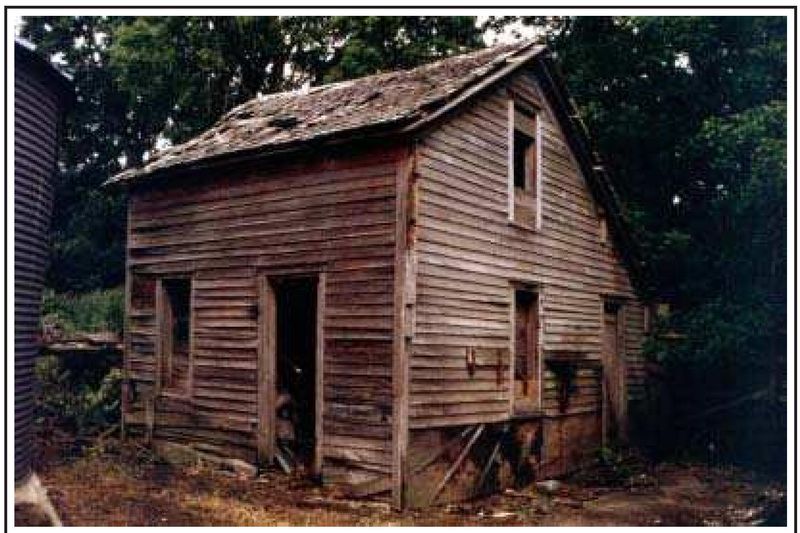

10. Lumber-Lined Luxury

During my research expedition through Oklahoma, I discovered photographs of what locals called “fancy dugouts”—earth homes with interior walls completely lined with salvaged lumber. These were the pinnacle of dugout luxury during the 1940s!

Homesteaders with access to sawmill scraps, dismantled crates, or old buildings would carefully line their earthen walls with wooden planks. This prevented dirt from falling constantly, eliminated the earthy smell, and created a more conventional living space.

The wooden interior also allowed for hanging pictures, mirrors, and shelves, bringing a touch of normalcy to underground living during challenging economic times.

11. Berm Houses

The first time I saw a berm house in Nebraska, I almost missed it entirely! These clever structures were built at ground level, then covered with earth on three sides and the roof, creating an artificial hill around a conventional structure.

Unlike true dugouts, which required excavation, berm houses were built using standard construction methods, then covered with earth for insulation. Many featured large south-facing windows that captured solar heat in winter while the earthen covering maintained cool temperatures in summer.

For 1940s homesteaders with limited tools for excavation but access to basic building materials, berm houses offered an ideal compromise.

12. Combination Rock-Sod Structures

“Use what you have” was my grandfather’s motto, and 1940s homesteaders embodied this principle with their combination rock-sod structures. These resourceful builders would use fieldstones for the lower portion of walls where strength was most needed, then switch to lighter sod blocks for upper sections.

This hybrid approach maximized limited resources while providing excellent durability. The stone base prevented moisture wicking from the ground, while the thick sod upper walls and roof provided superior insulation.

Families often plastered interior stone sections with clay to smooth surfaces and further improve insulation, creating surprisingly comfortable homes despite severe material shortages.

13. Earthship Precursors

Walking through New Mexico last spring, I stumbled upon what locals called a “tire house”—an early precursor to modern earthships. Some innovative 1940s homesteaders packed soil into discarded rubber tires, creating dense building blocks with excellent thermal mass.

These were stacked in a brick-like pattern and covered with adobe mud to form walls. The resulting structures maintained remarkably stable interior temperatures despite external fluctuations.

While not as refined as contemporary earthships with their sophisticated passive solar designs, these early experiments demonstrated the same core principles: using waste materials and earth to create self-regulating, low-cost housing during a time when conventional building supplies were scarce.

14. Prairie Dog Palaces

“We lived like prairie dogs,” laughed my elderly neighbor when describing her childhood home—a dugout with multiple underground rooms connected by short tunnels. Some ambitious homesteaders expanded their dwellings by digging additional chambers branching off from the main room.

This created separate spaces for sleeping, food storage, and living while maintaining the thermal benefits of underground construction. Ventilation was provided by small air shafts that doubled as emergency exits.

Children particularly enjoyed these warren-like homes, which felt like elaborate playhouses with their secret passages and cozy nooks, bringing a sense of adventure to what was born of economic necessity.

15. Adobe-Enhanced Earthen Homes

The most beautiful dugouts I’ve seen in historical photographs were those finished with adobe in the southwestern states. Homesteaders would dig their initial shelter, then gradually improve it by adding adobe brick walls at the entrance or applying thick adobe plaster to interior surfaces.

The clay-rich adobe created smooth, easily maintained surfaces that could be whitewashed or colored with natural pigments. Women often decorated these walls with painted designs or pressed flowers for a touch of beauty amid hardship.

The combination of earth-sheltered construction and adobe finishing created homes that were not only practical but aesthetically pleasing—a small luxury during difficult economic times.

16. Cellar Door Dwellings

During my historical society volunteer work, I cataloged photographs of what locals called “cellar door dwellings”—an ingenious adaptation of storm cellar entrances. Resourceful homesteaders would expand the typical sloped storm cellar doors into a larger framework covered with sod or earth.

This created a distinctive A-frame entrance to their underground home while providing crucial protection from harsh weather. The angled design naturally shed rain and snow while being easier to construct than vertical walls.

Inside, the sloped ceiling created storage space along the sides where ceiling height was insufficient for standing, making efficient use of every available inch in these humble dwellings.

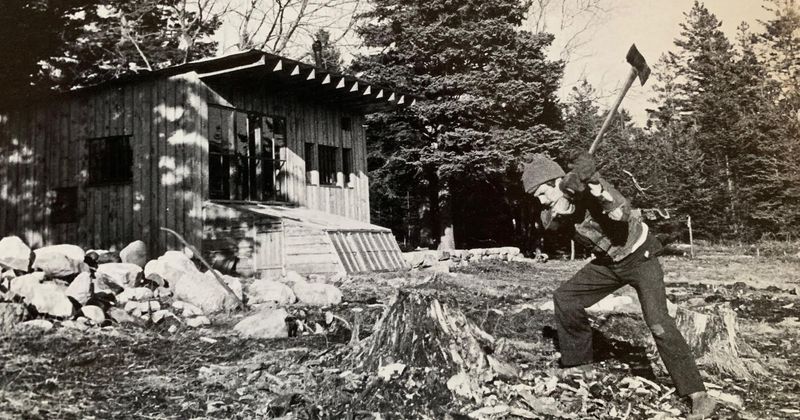

17. Sunken Log Cabins

The most fascinating hybrid structures I’ve researched were sunken log cabins—a clever compromise when timber was limited but earth was plentiful. Homesteaders would dig a rectangular pit about 3-4 feet deep, then construct a much shorter log cabin within this depression.

This approach reduced the number of logs needed by 30-40% while gaining the insulating benefits of earth-sheltered living. The roof typically extended to ground level and was covered with sod for additional insulation.

Windows were placed high on the walls, just above ground level, allowing natural light while maintaining the thermal advantages of being partially underground.

18. Straw Bale Augmented Dugouts

My favorite historical renovation technique involved straw bale additions to existing dugouts. As homesteaders gradually improved their circumstances, many would build straw bale extensions onto their underground dwellings.

These highly insulating walls were constructed by stacking compacted straw bales like giant bricks, then covering them with thick clay plaster. The resulting walls were up to 23 inches thick with insulation values exceeding most modern construction.

This combination of earth-sheltered and straw bale construction created remarkably comfortable homes that stayed cool in summer and required minimal heating in winter—a crucial advantage when fuel was scarce and expensive.

19. Bottle Wall Wonders

The first time I saw photographs of bottle walls in 1940s dugouts, I couldn’t believe my eyes! Creative homesteaders would collect discarded glass bottles, embed them in mud or adobe walls, and create beautiful light-catching features that doubled as insulation.

These bottles acted as small windows, allowing colored light to filter into otherwise dark dugout interiors. Common patterns included sunbursts, crosses, or simple geometric designs that transformed humble dirt walls into artistic statements.

Beyond their beauty, the air space inside each bottle provided additional insulation value, improving comfort while showcasing the remarkable creativity born of necessity during challenging economic times.

20. Salvaged Material Masterpieces

“Nothing goes to waste” was the mantra that produced the most eclectic dugouts I’ve studied—homes constructed from an astonishing variety of salvaged materials. During my archival research, I discovered photographs of structures incorporating automobile parts, packing crates, railroad ties, and even metal advertising signs.

Homesteaders would use car hoods as rain deflectors above doorways or flatten tin cans to create reflective interior wall coverings that maximized precious lamplight. Wooden shipping crates were disassembled to frame windows and doors.

These patchwork dwellings represented the ultimate in resourcefulness during a time when commercial building supplies were either unavailable or unaffordable.

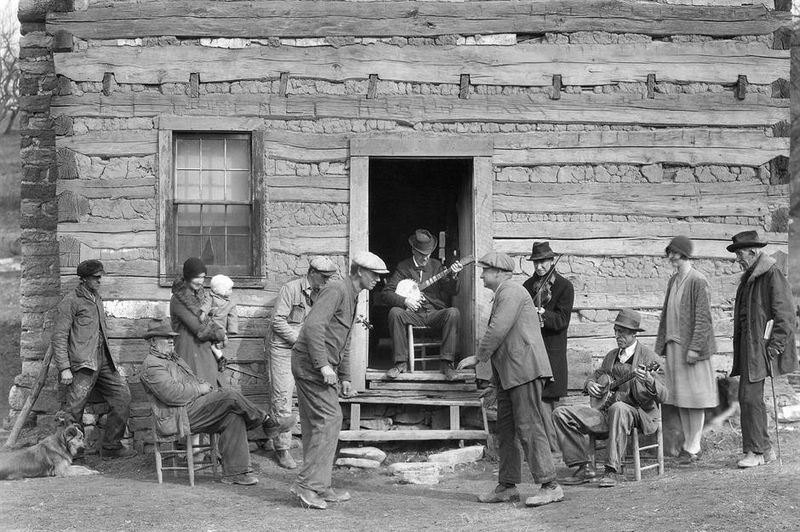

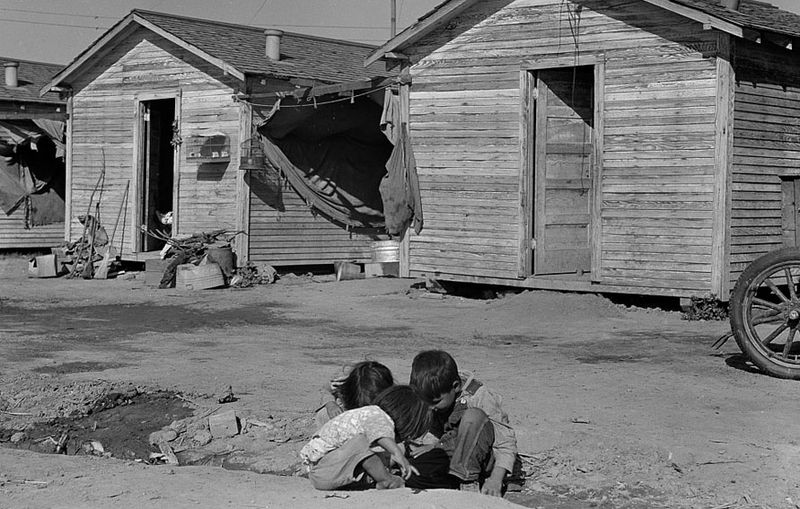

21. Communal Dugout Compounds

The most heartwarming structures I’ve documented were communal dugout compounds where multiple families worked together for mutual benefit. Several related families or close-knit neighbors would construct individual dugouts around a shared central courtyard.

This arrangement provided protection from wind, created a safe play area for children, and facilitated resource sharing during difficult times. Communal outdoor kitchens, baking ovens, and washing areas reduced individual workloads and conserved precious fuel.

These compounds fostered strong community bonds and exemplified the cooperative spirit that helped many Americans survive the economic challenges of the 1940s through shared labor and resources.